While the Morgan horse was the star of the equine show in northern New England, and just a little before the Quarter Horse went West, the American South was producing its own type of horse and its own style of riding. What we now call Saddle Seat has strong proponents in the Morgan show world, and it’s a significant part of Arabian showing as well. But the horses bred and designed for it came out of Kentucky and Tennessee and the rest of the Southern states.

The Tennessee Walking Horse is now the state horse of Tennessee. Its cousin the American Saddlebred is a direct descendant of the “American Horse,” a combination of various breeds and types including the Thoroughbred, the Narragansett Pacer, the Canadian Pacer, and the Kentucky Saddler. The breeders’ goal was to produce a tall, elegant, refined but substantial animal with glass-smooth gaits, a preeminent saddle horse and also a spectacular show horse. (With bonus SFF connection: William Shatner has shown Saddlebreds for many years.)

These were aristocrats of the riding world and, to a somewhat lesser extent, of fine harness—driving horses with flash and style. Racing speed was not a priority. They were meant to be ridden around plantations, in parks and in the show ring. In the American Civil War, Kentucky Saddlers were the cavalry mounts of generals. Lee’s Traveller, Grant’s Cincinnati, Sherman’s Lexington, were all Saddlers. What the Iberians and the Lipizzans were to European nobility, the Saddler was to the American equestrian elite.

The saddle developed for and by these breeds is distinctive. It’s almost completely flat, and sits well back, making space for the long, high, arched neck and huge, free shoulders with their high, flashing knee action. It’s as different from the Western saddle as it’s possible to be.

Staying in a Saddle Seat saddle requires the rider to be very well balanced. There’s very little to keep her in it—minimal rise fore and aft, and minimal padding. A truly fine Saddle Seat rider is extremely elegant with her long stirrups and her high, still hands—controlling the horse with minuscule flexions of the fingers on the double set of reins.

Smoothness of gait is a must. The Saddlebred comes in two flavors, three-gaited and five-gaited. The former moves like most other horses, in walk and trot and canter. The latter adds a pair of additional gaits, the slow gait and the rack.

The Tennessee Walker is a full-on gaited breed, famous for its running walk, along with the flat-footed walk and the canter. Some may trot, and some will pace, but the running walk and the canter are the signature gaits of the breed.

Gaited horses are wired differently than non-gaited. Their movement is different; whereas most horses have a four-beat walk, a two-beat diagonal trot, and a three-beat canter (plus the four beats of the gallop), the gaited breeds add in all sorts of different types of stride. What they all have in common is smoothness. The walk and canter are generally pleasant to ride, but the trot can rattle your bones. It’s strongly up-and-down and can be a serious challenge to sit—hence the invention of posting, named after the British post riders who developed it in order to survive their mounts’ brisk and ground-devouring trot.

Buy the Book

Fate of the Fallen

The various forms of gaited movement are a godsend for a rider’s comfort. They allow a horse to move at speed without jouncing or jarring, and a well-trained, fit gaited horse can keep it up for miles—versus the canter and gallop, both of which can’t be sustained for any great distance without wearing out the horse, and the trot, which can go on and on but asks a great deal of the rider.

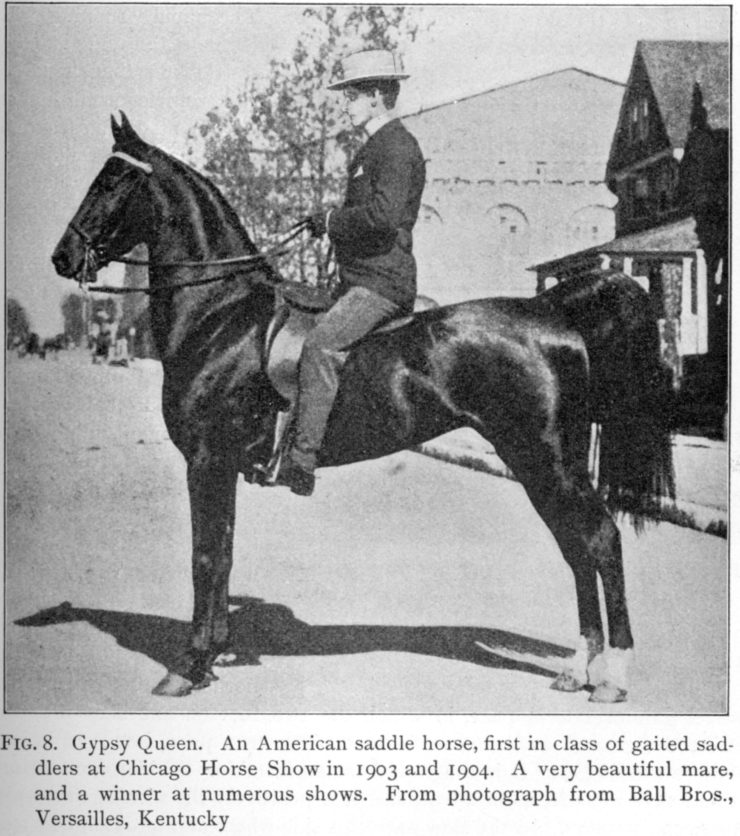

The original saddle horses were bred for riding long distances. The advent of the show ring in the nineteenth century added a further element of flash to the mix. Horse shows were and are tests of a horse’s ability to perform, and they’re also beauty contests. They’re meant to show off the ideal of the breed or discipline, which in the case of saddle seat means charisma and fire—and spectacular gaits.

Both the Saddlebred and the Tennessee Walker, on their own, are beautiful horses, and versatile. Though they’re best known as show-ring stars, they make nice dressage horses (provided they will trot—trot is important in dressage), trail horses (that running walk is awesome on the trail), driving horses, even hunters and cow horses. A rider has to know how to ask for the extra gaits, but the rack and the running walk are built in. A gaited horse is born that way.

Unfortunately, as all too often where animals, money, and glory intersect, over time the horse’s natural gaits, look, and way of going have stopped being enough to win show classes. People have fixated on narrower and narrower ranges of looks and gait, defined more by fashion than function, and more and more extreme versions have become the norm, until in some classes it’s not possible for a horse in his natural state to even compete.

At minimum it’s extreme grooming: clipping the whiskers (which serve the same function as those of a cat), clipping out the insides of the ears (leaving them vulnerable to flies), shaving the long hairs of the fetlocks, cutting off all or part of the mane. That’s mostly cosmetic. But then there’s the fashion with Saddlebreds for a particular set and angle of the tail that does not exist in nature. A ligament will be cut to “relax the back,” then the tail is set in a harness and fluffed out with a bustle. Harmless, we’re told. Doesn’t interfere with fly-swatting capability. Makes the horse look pretty. He has to live in a tailset, but its proponents believe it’s worth it to have the right look in the show ring.

If that’s not enough, there’s always ginger around the rectum—the pain causes the horse to flag his tail up and away. Makes him move with more animation, too. This is banned, but can be hard to stop.

And there there’s the modification of the gaits. Adding weight to a horse’s legs and feet causes him to lift them more briskly. Heavy shoes are the start of it. Building up the hoof to extreme levels through judicious trimming and shaping, adding blocks and pads. Devices and preparations that cause sores on the lower legs, which make the horse snap up his knees more sharply to get away from the pain.

These things escalate. Extremes become the norm. Trainers add more and more and more weight and pain, for more and more exaggerated movement, and show judges reward it and competitors emulate it and everybody tells each other that this is beautiful. It spirals up and up and up, until no one remembers what the original animal was supposed to look like.

I’m not going to link to the ultimate manifestation of this trend. If your stomach can take it, search on “Big Lick Walkers.”

Some breeders and owners and competitors have pushed back, with the aid of animal welfare groups. Some have managed to get laws passed against soring and other extreme techniques and devices. There’ve been movements toward a more natural look and way of going, and classes for horses in ordinary flat shoes (or even barefoot).

It’s an uphill battle, but people who really care about the horses are willing to keep fighting. They’re focused on preserving these breeds as they were meant to be.

Photo by Charles Plumb, from Types and Breeds of Farm Animals (1906, public domain) via Wikimedia Commons.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks by Book View Cafe. She’s even written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. Her most recent short novel, Dragons in the Earth, features a herd of magical horses, and her space opera, Forgotten Suns, features both terrestrial horses and an alien horselike species (and space whales!). She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.